Context, intent, change, purpose, constraints - a model for communicating requirements

This post was originally posted on the Mind The Product blog.

We’ve been doing some thinking over the last few months about how we communicate ‘requirements’ to teams. I put ‘requirements’ in inverted commas because part of the debate is whether they’re even the right thing to communicate. Should we be telling engineers, designers and other specialists what we ‘require’, or what the problem is that they should solve? Are those the same thing? Do we communicate in ‘user stories’ or via some other means?

When we’re asking people to design and build software products, there’s a tricky balance to be struck. On the one hand, as I’ve certainly learnt from painful experience, failing to be clear about every detail can end up in a product that doesn’t quite do what I expected. On the other hand, trying to define every aspect of a product before we start building it risks taking autonomy away from the very smart and knowledgeable people doing the actual building, and missing the opportunity to discover better approaches as we go.

Can we learn anything from the military?

The military might seem like an odd place to look for inspiration in solving this challenge. In tech products we often see ourselves as much closer to, say, the construction industry - with our architecture, engineers, prototypes, and talk of ‘building’ things. But I’m not sure that’s always the best analogy. Construction demands precise plans documented up-front, with specialists delivering exactly what’s been asked for, to exacting tolerances, with little room to adapt on the fly - exactly the approach we’re trying to avoid.

Compare that with a military operation which (despite the phrase ‘planned like a military operation’ tending to imply a high degree of precision and control) intentionally builds in flexibility and adaptability at every stage. Above all, it recognises the benefits of allowing decisions to be made as late as is safe to do so, and at the lowest level possible. What goes hand-in-hand with that is a finely-honed process for imparting the information that people need to be able to make decisions and act with autonomy.

The military orders process

Military orders follow a precise structure, and can be pages and pages long (or take hours to deliver in person), yet within them there is really only one line that specifically tells each junior commander what they must do. Often only a few words long, they’ll read as something like ‘Defeat the enemy position at XYZ, in order to enable the company advance to ABC’.

Everything else is about providing that junior commander with what they need to best decide how they’re going to go about that task.

I won’t go into every intricacy of the orders format, but at a simplified level it consists of:

A ‘situation’ section, which provides detail about the background to the operation, the terrain, what friendly and enemy forces are doing, and so on. This obviously provides the recipient of the orders with critical information to guide their decision-making.

A section that lays out what the commanders at one and two higher levels (‘one-up’ and ‘two-up’) have been asked to do, what their missions are and - crucially - what their intent is. This means our more junior commander is not thinking just about the task they have been given, but how it plays in to the wider mission and how they might contribute to achieving the intent of their higher commanders, not just following the letter of what they have been told to do.

The specific tasks, as I’ve outlined above. But, as you might have noticed, even within that they contain both a clear direction but also an ‘in order to’ statement, that explains why that task has been set, and what the purpose of it is.

Coordinating instructions and control measures, which include all sorts of details like equipment, radio frequencies, and also boundaries within which the commander must operate. For example; a time by which the operation must be complete, grid lines that they must not stray outside, and so on. These set parameters within which they can operate, and give them freedom of movement and autonomy within those parameters, rather than having to tell them exact where to go, and when.

As I say, that’s over-simplified, but the more I think about the question I’m trying to answer about how to communicate technical requirements, the more I like this model. The above is, really, the same information – I would argue – we need to be communicating to engineering teams. So maybe, instead of worrying about what we call it (requirements, user stories, specifications, etc) we focus on the information we’re trying to impart.

A civilianised model

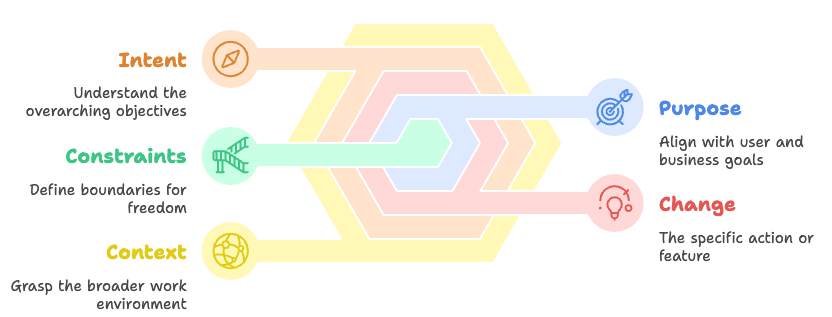

If we civilianise it, here’s what I think we’re aiming to communicate:

Context - teams can produce better work when they understand the context around it. How does it fit into a wider programme of work? Is it linked to what other teams are doing? Is there market or competitor research that has informed it?

Intent - this is especially key, I think. Explaining what we’re trying to achieve, and perhaps what the company, portfolio or department is also trying to achieve, gives the team the opportunity a) self-check themselves and identify where what they’re building risks not achieving that goal and b) suggest ideas that might better achieve it, especially if things start to go a bit wrong and the original plan turns out not to be viable, that’s when understanding intent gives us freedom to adapt and overcome.

Change - the change, or ‘what’ we are trying to do, is almost the smallest piece. It could be the middle part of a user story (‘I can do xyz’) a proposed feature name, an outline solution, or something else. The key, I think, is that the better we flesh out the bullet points above and below this one, the less specific this change needs to be.

Purpose - the ‘in order to’ bit. This is already built into user stories, in some respects (the ‘so that…’ part) although it’s worth understanding not only the purpose for a user but also for the business, as the two might be different.

Constraints - constraints could be in the form of acceptance criteria, or just a list of constraints, but what’s essential is to think of them not as ‘follow this line’ but as ‘don’t stray outside these lines’. If that seems like a small distinction, it isn’t. Good, well-considered constraints actually create freedom by providing a clear area within the constraints in which the team can operate with confidence. That’s very different to constraints (or acceptance criteria, or requirements, or anything else) that are just another way of telling them exactly what to do.

I don’t know if this is perfect, but I’m excited to discuss it with my teams as a way to think about communicating requirements. Many teams will probably already be confidently doing all of the above through their existing PRDs or user stories, but if you are struggling a bit to figure out how to communicate requirements then maybe going back to basics and breaking it down to a list a bit like the one above could help.

Do let me know what you think. And, if you’re enjoying these blog posts, I’d love you to help me grow my subscribers by sharing them with anyone else you think might be interested.